- ABOUT US

- PROGRAM AREAS

- CONSERVATION APPROACH

- EDUCATION

- MULTIMEDIA

- the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA),

- the National Park Service,

- the Environmental Protection Agency,

- the U.S. Geological Survey,

- the National Aeronautics and Space Administration,

- the Puerto Rico Coral Reef Monitoring Program, and,

- the Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System.

How can we make coral cover data more accessible and usable?

By Erica K. Towle, Ph.D., National Coral Reef Monitoring Program Coordinator

Have you ever thought about how coral cover data are collected from different agencies and programs that work on coral reef ecosystems? Do scientists from each program know what data other programs are collecting?

Have you ever thought about how those data get used after they are collected? What about how they are stored? And how someone might use the data again in the future?

The truth is, scientists don't always do a great job making it obvious how we collected our data, and where you can find our data. On top of that, scientists don't always do a great job talking to one another about standardizing the format of the data so that it can be compared to other datasets.

Why do all these data questions matter? Coral reefs are threatened due to a lot of factors including climate change, unsustainable fishing practices, and land-based sources of pollution. In order for decision and policy makers to really understand the status and trends of coral reef ecosystems, we need the data to be accessible to data analysts and in the same format so it can be compared to other datasets. That way, we can do analyses that help us really understand coral health so we can make science-based management decisions.

But, if lots of different programs and agencies are collecting data differently and aren't really coordinated, how can we hope to improve these issues?

Well, it just so happens that there is a committee called the Interagency Ocean Observation Committee (IOOC), which was chartered by the White House specifically to address issues like this. The objective is to make recommendations on matters related to ocean observations across the federal government. Ocean scientists and decision-makers often struggle to communicate well with each other, and by linking national and regional ocean observation groups, the IOOC seeks to enable improved understanding and management of our ocean resources, like coral reefs.

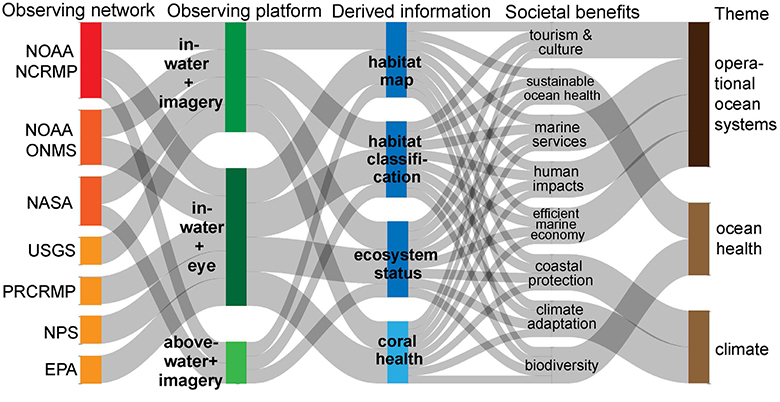

So, for the first time at the U.S. federal government level, a group of experts including coral scientists and data managers from across five U.S. federal agencies and two regional groups came together over the course of one year to better understand the ways that coral cover data are collected in the U.S. and try to improve the ways the data are stored, made public, and analyzed.

The group consisted of members from:

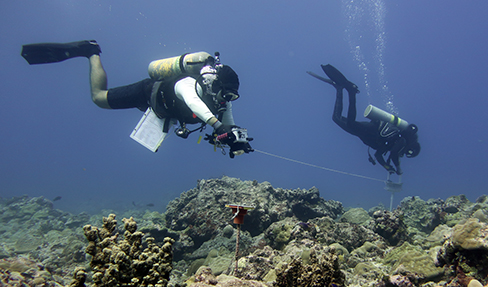

The IOOC chose to focus on coral cover data because of the urgent need for coral reef conservation and management, and the global, national, and regional scale of coral reef data collection. The goals of the team were to first identify the programs consistently collecting coral cover, their methodologies, and the management rationale for collecting the data. Special focus was given to highlight where programs were collaborating well together, as well as where there were gaps in data collection, both in time and space. The team spent a lot of time understanding the extent to which data were standardized and comparable with each other (i.e., how the data were measured and formatted).

About halfway through the year-long process, the team began making recommendations for improvements based on the information gleaned during the first part of the year. FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) data principles were used as the guiding framework for the recommendations. In other words, recommendations were focused on improving the way someone can find a data set, get access to it (download it), use it in their own analyses, and allow others to re-use it in the future.

The process did, in fact, highlight that major improvements need to be made on data interoperability, in other words, the ability to combine datasets across various agencies and programs.

As a direct result of that finding, the group made recommendations on how to improve data standardization by using Darwin Core Standard formatting. Darwin Core is a data standard that defines consistent names for data parameters that are common to most biodiversity datasets. Using consistent names makes it easier for people to understand that, for example, a value in dataset A is the same as dataset B because they have been defined the same way. What using Darwin Core actually looks like in practice is using a standard file format in the form of a ZIP file that contains interconnected text files and enables the data collector to share their data using common terminology. This standardization not only simplifies the process of making the data public, it also makes it easy for users to discover, evaluate, compare, and combine data.

So, why haven't we been doing this all along?! Good question, but it boils down to the idea that different scientists have different ways of organizing their data as well as slightly different terms for different metrics, etc. In a nutshell - there is a lot of inconsistency in how data is organized. But the idea is that if we can reduce that inconsistency, we can greatly improve the ways we share data and ultimately the way we use it.

The group also recommended greater coordination and communication across the U.S. federal agencies and regional groups collecting hard coral cover data via pre-existing groups like the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force. For more detailed recommendations, see the full report which is linked below.

The implication of the report recommendations is the ability to more easily re-use data collected from different projects for a variety of coral reef management needs. If all programs and agencies adopted the recommendations, there could be seamless and consistent reporting and a more accurate understanding of the status and trends of coral reef ecosystems at broad geographic scales . Also, the recommendations are key to making data products and tools that inform coral-related federal government priorities, such as strengthening nature-based coastal protections and lessening the effects of climate change.

So, what's next? The authors will make sure the report recommendations reach a broad audience within the IOOC network and beyond so that people can understand the importance and value of implementing these recommendations. Then begins the hard work of truly committing to a future of data standardization. It can be hard to break old habits. But when we realize that the benefits of standardization mean having better, more informed answers to questions about the natural world, then the choice to undertake data standardization efforts becomes an easily accomplished task.

To learn more about the task team, visit the IOOC website.

To read or download the full report, visit the open access Zenodo archive.

For questions, email Erica Towle

Related Stories and Products

About Us

The NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program was established in 2000 by the Coral Reef Conservation Act. Headquartered in Silver Spring, Maryland, the program is part of NOAA's Office for Coastal Management.

The Coral Reef Information System (CoRIS) is the program's information portal that provides access to NOAA coral reef data and products.

Work With US

U.S. Coral Reef Task Force

Funding Opportunities

Employment

Fellowship Program

Contracting Assistance

Graphic Identifier

Featured Stories Archive

Access the archive of featured stories here...

Feedback

Thank you for visiting NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program online. Please take our website satisfaction survey. We welcome your ideas, comments, and feedback. Questions? Email coralreef@noaa.gov.

Stay Connected

Contact Us

NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program

SSMC4, 10th Floor

1305 East West Highway

Silver Spring, MD 20910

coralreef@noaa.gov